Insights at UBC Sauder

Responsible Leadership & Sustainability

Politics & Public Policy

Werner’s blog: Taking stock of Canada's GHG emissions at the start of COP28

Posted ─ 2023-11-30

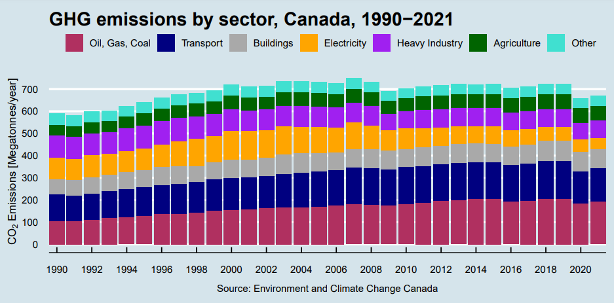

The first chart shows the overall picture for Canada. Since about the year 2000, emissions have

stagnated at 700 Megatonnes per year. Only during the pandemic year 2020 and post-pandemic

year 2021 were emissions down a bit more, and during the recession year 2008. So overall this

picture is not encouraging.

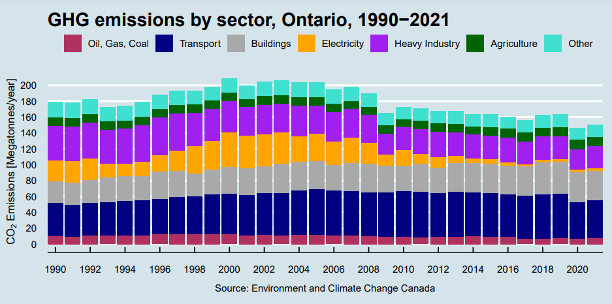

Let us turn to individual provinces, as climate policies differs substantially across provinces and

the federal backstop policy only kicked in fully in 2019. First up: Ontario. Canada's largest province

managed to phase out coal from its power grid, and this shows up in the orange bars starting to

shrink rapidly. Emissions from heavy industry have also decreased.

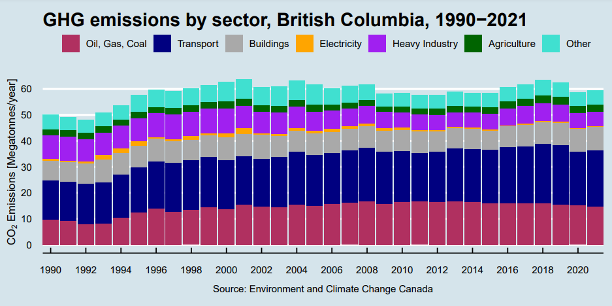

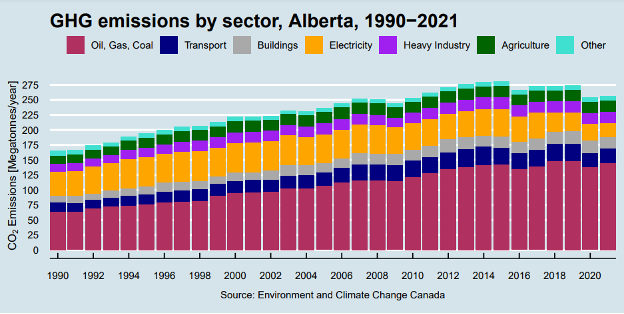

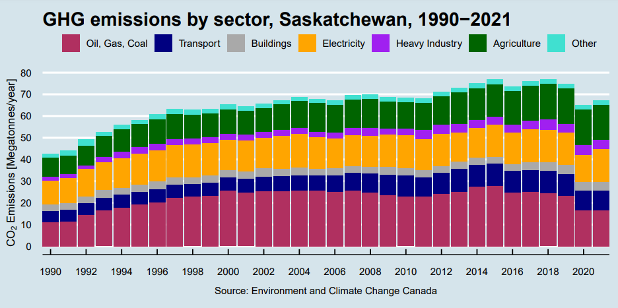

The province of Saskatchewan has Canada's largest footprint on a per-capita basis. The province

has higher emissions than British Columbia even though it only has a quarter of that province's

population. Saskatchewan has an oil and gas sector, it still relies heavily on coal for electricity

generation and it also has large emissions from agriculture.

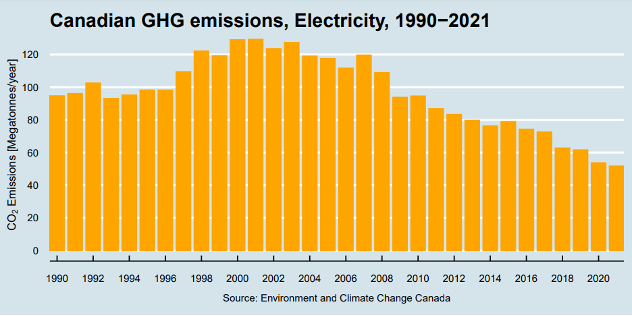

Let us return to Canada's overall emissions and look more closely at the industry-level emissions.

Let's start with Canada's only success story for greenhouse gas reductions: the electricity sector.

Mostly due to replacing coal with natural gas, emissions have been cut more than half. That is an

important accomplishment, and the next stage of replacing natural gas with renewable energy

sources is firmly in sight and is becoming increasingly affordable economically and feasible

technologically.

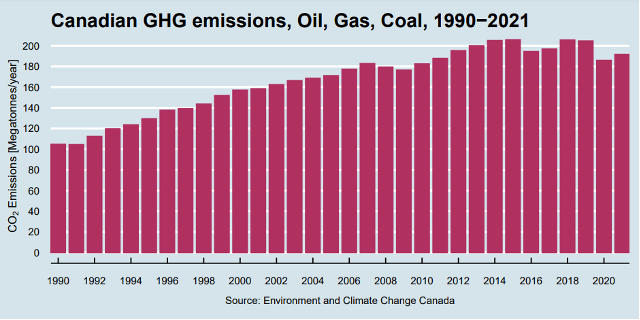

Canada's emissions from the oil and gas industry peaked at over 200 Megatonnes and have been

slightly dampened by the pandemic. Perhaps the good news is that emissions have reached a

plateau. It is clear that Canada will not be able to achieve its ambitions net-zero by 2050 goals

without addressing these emissions drastically. Carbon capture and storage will need to play a

major role to get these numbers down.

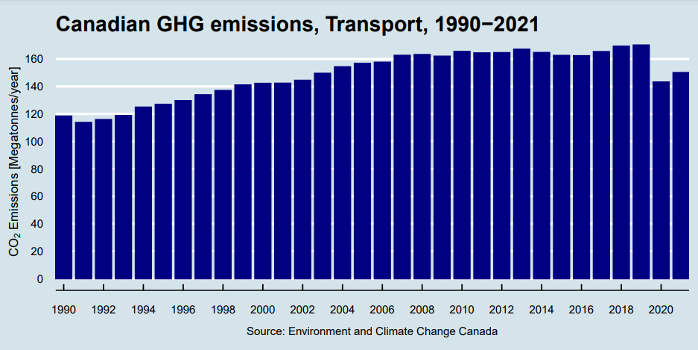

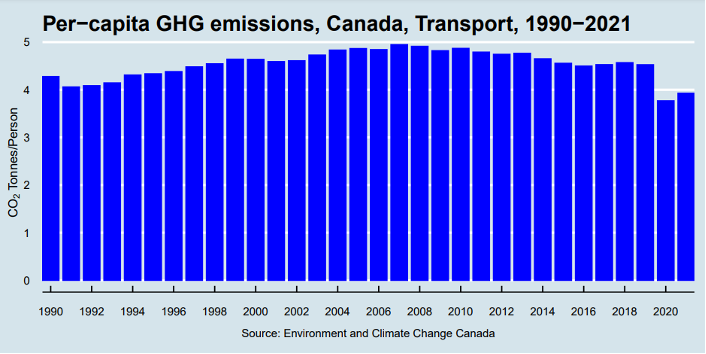

Transportation emissions, the bulk from personal transportation, can be decomposed into separate

scale, composition, and technique effects. The scale is determined by population size and annual

mileage per person. The composition effect captures transportation mode and vehicle fleet

composition. The technique effect identifies how the emission intensity of vehicles changes over

time. Public policy can affect all these components. A simple way of visualizing the major

components involves expressing transportation emissions on a per-capita basis, shown in the next

diagram. Here, the emission intensity is improving slightly since about 2006. Public policies seem

to have a positive effect, although only gradually because fleet turnover is slow and driving

behaviour is relatively price-inelastic. Canada's ZEV mandate is likely going to change this picture

dramatically over the next decade.